Ashik Kahina

Reading Periyar today

31 March, 2021

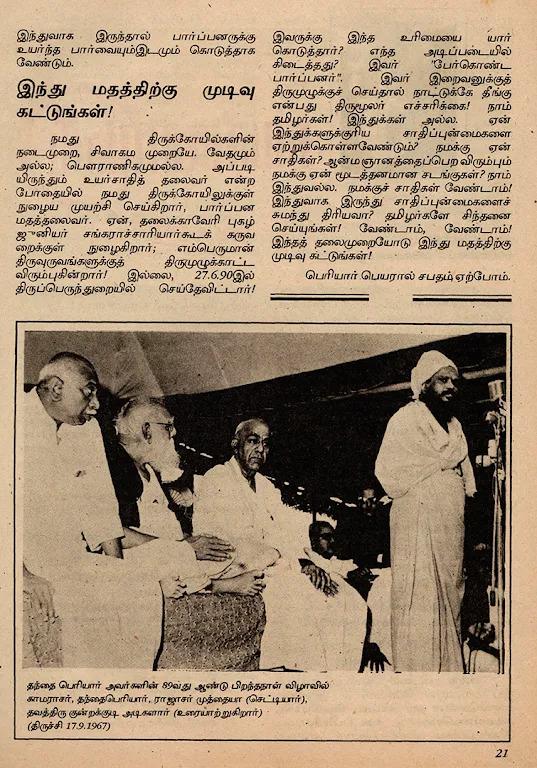

IN 1957, a special-forces inspector in Tiruchirappalli filed a case against EV Ramasamy—the founder of the Dravidar Kazhagam, popularly known as Periyar—under Section 117 of the Indian Penal Code. Section 117 forbids the abetment of an offence by ten people or more, and is punishable with three years of imprisonment. Periyar, 78 years old at the time, was charged for allegedly urging people to kill Brahmins and set fire to their houses, and for burning sections of the Indian Constitution at a public demonstration. A sessions judge sentenced him to six months in prison.

In the three speeches submitted to the trial court for review, all of them given in the first three weeks of October that year, although Periyar did not urge anyone to kill Brahmins or burn their houses, he announced his intention to burn the Constitution in public and explained clearly his reason for wanting to do so. He even listed the exact parts he wanted to burn: Article 13, Section 2; Article 25, Section 1; Article 29, Sections 1 and 2; and Article 368. They are, he said, a mess of contradictions: the article that states all citizens may freely practise and propagate religion is at odds, he said, with the laws that protect minorities or grant them entry into all institutions maintained by the government and the right to preserve their distinct culture and language.

In one of the speeches, published in the magazine Viduthalai, Periyar said:

Let the government make a law that there will be no “Brahmin” caste and that, even if there is, they won’t be allowed to live as Brahmins. Of the six who made the Constitution, four are Brahmin; most of the unelected members of the Constituent Assembly are from the Congress Party. This law protects Hinduism. Hinduism protects caste; its whole point is to protect caste. There is no easy way for an annihilator of caste to modify it; he has no chance. (Read Article 368.) So what can we do, those of us who want to annihilate caste, those of us who want an independent Dravidian nation, those of us who want to protect Tamils from exploitation? What way do we have to show our opposition other than setting fire to it?

In Tamil Nadu in 1957, as in the present day, untouchability was widely practised. Not everyone was allowed to enter or work as priests in temples; manual scavenging and bonded labour were commonplace; there were no separate electorates to protect minorities; reservations in government jobs and education were paltry and inconsistently implemented. Periyar urging people to burn parts of the Constitution, rather than people or their houses, showed a commitment to non-violent protest. When he said there should be no Brahmins, he meant that there should be no caste, not that the men and women who called themselves Brahmin should be exterminated. When he said they should not be allowed to live as Brahmins, he meant that they should not be allowed to practise untouchability. That the nuance of his argument was lost on the inspector who filed the case and the judge who reviewed it is no surprise. What is surprising is that the prime minister at the time, himself a Brahmin, misinterpreted Periyar similarly.

While Periyar was on trial, Jawaharlal Nehru visited Tamil Nadu. He did not go to Tiruchirappalli to meet Periyar, but talked about him in a speech in Madras:

But one of the most remarkable and one of the most foolish agitations that I have experienced in India has recently started in your own State of Madras. This I believe is known as Dravida Kazhagam agitation and the leader of this movement had said something which cannot be forgiven and which cannot be tolerated, Apart from actually talking in an unabashed manner about murder, inviting people to murder others—a thing unheard of in any civilised society—he has dared to insult the national flag and the national Constitution. These are unforgivable offences … I wondered recently if the Dravida Kazhagam in Madras is not more primitive than any primitive tribe in India. Because it talks a language which is a language unheard of in civilised society. It is a language of murder. It is a language which should either lead one to the prison or to the lunatic asylum, because society cannot tolerate that language and no civilised State will put up with a deliberate insult to its Constitution.

Nehru’s language paints clarity and reason as murderous aggression, and human beings as threatening animals that need to be locked away in cages. Periyar was not the only one imprisoned after the demonstration. Over three thousand people went to jail. Around eighteen of them died in and out of custody.

Today, the decline of democracy in India is often written and spoken about as though the subjection of the majority of its people to a small alliance of upper-caste Hindu politicians and industrialists has just begun. But Periyar is among the prescient few who saw it coming a century ago. His writings and speeches reveal that he was not, as is often said, a supporter of British colonialism, nor was he a warrior serving his Aryan-embattled mother tongue—which was not, in fact, Tamil—and motherland. He simply saw that Independence, for the majority of India’s people, was a passage from one form of subjugation to another. Like Ambedkar and Jotiba Phule, his aim was the annihilation of Hinduism and its caste system, which, he argued, was reproduced and kept alive by endogamous marriage. Unlike Ambedkar and Phule, he suggests that a society free of caste and religion can only be achieved through the annihilation of the nation state. His legacy has kept Tamil Nadu from the cultural hurt and pride that Hindutva forces have successfully exploited almost everywhere else in the country. Now that the broad opposition to Hindutva is being forced, increasingly, to concern itself with the continuity and unity between the liberal and right-wing variants of Indian nationalism, Periyar’s legacy is vital and relevant, not just to Tamil society but to the entire country.

DESPITE HIS LOOMING PRESENCE IN INDIA’S HISTORY and his significance to thinking about the Indian present, little attention is paid to Periyar outside the Tamil sphere. The English media’s attitude to Periyar remains one of neglect and condescension. Last year, he was briefly in the news, after statues of him were vandalised with saffron dye in Tiruchirappalli and Coimbatore, as well as after the actor Rajnikanth’s public condemnation of a 1971 DK rally at which statues of Ram and Sita were allegedly paraded naked. Media outlets at the time had to post “explainer” videos introducing him to readers.

The more sustained writing about Periyar in the media criticises him for “hate-mongering” against Brahmins. The most ubiquitous writer in this vein appears to be PA Krishnan. In a 2017 article for The Wire, titled “Why do Dravidian Intellectuals Admire a Man as Prickly as Periyar?,” which sparked an extended debate, Krishnan makes parallels between the Dravidian Movement to Hitler and Brahmins to Jews in Nazi Germany:

Periyar and his disciples ... attributed – exactly like Hitler did with the German Jews – grand conspiracies and clever manipulations by Brahmins for the plight of the non-Brahmins. It did not ever occur to Periyar that independence would open the sluice gates of education and other opportunities. He wanted the British to continue to remain in power – while simultaneously complaining that they were succumbing to the machinations of the Brahmins.

The comparison Krishnan draws is old and very popular. Brahminical victimhood in Tamil Nadu has long articulated itself as a feeling of having been singled out among a wide spectrum of oppressors and being given sole blame. Paradoxically, Brahmin critics of Periyar usually praise Ambedkar, who wrote unequivocally in Castes in India: “Why did these sub-divisions or classes, if you please, industrial, religious or otherwise, become self-enclosed or endogamous? My answer is because the Brahmins were so.” In their meticulous and impassioned response to Krishnan—also published in The Wire—the scholars S Anandhi and Karthick Ram Manoharan attempt to explain this tendency:

The love of the Hindu right for Ambedkar has several reasons, key being their utilitarian strategy to accommodate Dalits into their fold. But their visceral hatred for Periyar hinges on one crucial aspect of the iconoclastic leader—his criticism of the legitimacy of the Indian state. Periyar and Ambedkar shared a lot of common ground: their advocacy for universal education, women’s rights, annihilation of caste and so on. One could also say that Ambedkar’s criticism and rejection of Hinduism was more theoretically intensive than that of Periyar. Periyar, however, rejected the nation-state and its ideology, either in its ‘secular’ or ‘communal’ manifestations. Hence, Periyar remains untouchable and ‘anti-national’.

Aravindan Neelakandan, a frequent contributor to Swarajya; H Raja, a former BJP member of the legislative assembly; and Subramanian Swamy, an economist and BJP member of parliament, are three examples of members of the Hindu Right who praise Ambedkar and revile Periyar. As the scholar Anand Teltumbde shows in his book Hindutva and Dalits, the Hindu Right has, to an extent, been able to refashion and appropriate Ambedkar’s legacy for right-wing nationalism. The same has not been attempted with Periyar, not just because he was a more brazen critic of the nation state, but because the critique of nations was more central to his thought.

In the world of Tamil letters as well, Periyar’s legacy has been called into question. Beginning in the 1980s, a stream of books and essays have emerged arguing that Periyar—and Dravidian politics itself—were anti-Dalit. Tamil social media affirms that this line of criticism remains alive and strong. The most notorious attack in this vein came from incumbent DMK MP Ravikumar, who argued, most famously in a piece in Outlook titled “Periyar’s Hindutva,” that the opportunism of later Dravidian politics and systemic anti-Dalit violence, which has only escalated since the 1990s, already had their roots in Periyar’s movement. The Brahmin and Dalit attacks against Periyar share a method: ill-supported generalisation, bolstered by a few quotes meant to shock readers. For instance, Ravikumar, claiming Periyar ridiculed Dalit leaders who fought for reservation, quotes him as saying, “Asking the government for jobs, education, duties, huts and housing; and seeking from the Mirasdars two extra measures of paddy will not help in anyway.” But this is not ridicule. Periyar was saying that social transformation will not come from bargaining with the political and landowning classes.

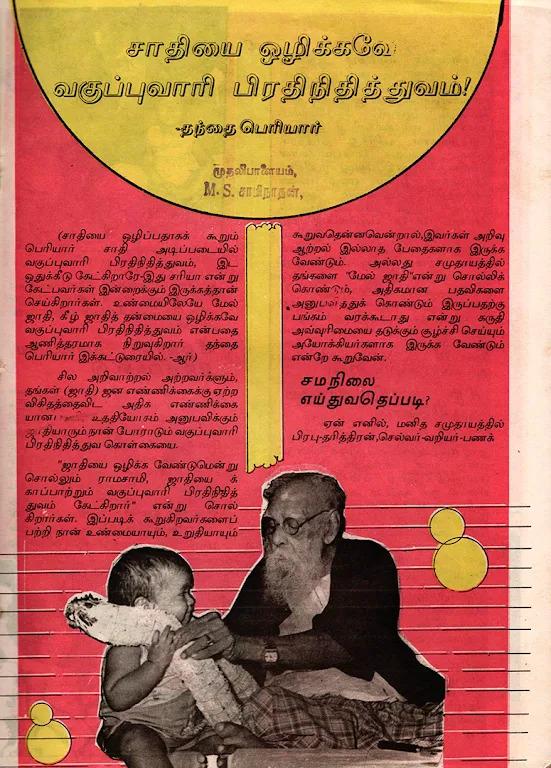

Periyar’s ideas are neither easy to generalise nor capture in a few quotations. His political life began when he joined the Indian National Congress at 40 years of age, and only ended when he died in 1973 at the age of 94. For over fifty years, he wrote, organised and gave speeches, with few breaks. Much of what we call his “writings” are speeches, or fragments of speeches, transcribed and filtered by anonymous others; his 40-volume “collected” works are by no means his complete works. We are still waiting for the sustained engagement and nuanced critique that his archive deserves.

Part of the reason a comprehensive critique of Periyar remains elusive has been the lack of access to Periyar’s speeches and writings. It was only in 2017 that a comprehensive, substantial and affordable anthology, titled Periyar Inrum Enrum—Periyar: Now and Always—was published by Vitiyal. The book has already passed its tenth printing. In English, it remains difficult to get an extensive idea of Periyar. A five-hundred-page selection of his writings and speeches (misleadingly titled Complete Works of Periyar E.V.R), translated into English by the current DK President, K Veeramani, is available for free on Velivada, but the translation is often imprecise and does not capture the vernacular force of his writings. The ubiquitous small pamphlets in English that compile quotations from Periyar’s works around a given subject—Islam, patriarchy, village reconstruction—published by the DK-run Periyar Self-Respect Propaganda Institution and distributed by a wide range of movements in Tamil Nadu are no better translated and present his thoughts out of context.

In three hefty books written over more than a decade of archival work, V Geetha and SV Rajadurai have given us a more intricate analysis of the relation between Periyar’s life, thought and context than can be found anywhere else. Two of them—Cuyamariyatai Camatarmam and Periyar August 15—are in Tamil. The third (not a translation of either of the Tamil books), Towards a Non-Brahmin Millennium, draws from its Tamil counterparts, but offers a less detailed and broader account. Cuyamariyatai Camatarmam details with minute precision the genealogy of Periyar’s thought from his beginnings as a Gandhian to the leader of the movement for a separate Dravidian state. August 15, as the title suggests, focusses on the movement against Indian independence, elaborating in great detail the national and international circumstances that made it necessary. It has now been over twenty years since the last in the series was published, and we are still waiting for the book that reinterprets Periyar for the present.

ACCORDING TO SAMI CHIDAMBARANAR’S BIOGRAPHY, Periyar’s father, Venkattar, had been forced by the early loss of his parents to spend the first half of his life living by coolie work. He eventually managed to open a small convenience store, which, at the height of his prosperity, he enlarged to a general store. But he was unable to enjoy his wealth because he and his wife could not have children—their first two died and it was to be a decade before they had their first son. Their experience of precarity and scarcity made them strict adherents of Vaishnavism, and their house was crowded with pandits, saints and astrologers, who took Venkattar for a significant portion of his wealth.

Born in Erode in 1879, Periyar was exposed to, and found difficult to accept, Brahminical rituals, texts and practices from a young age. Before he turned ten, his parents took him out of school for eating and drinking water at his Chettiar classmate’s house. By the age of 12, he had been put to work for the family business. He was closer to the house and had many disputes with the Brahmins that flooded it. Chidambaranar narrates one such dispute:

There was a Brahmin called Ramanadh Iyer who had a shop in front of EVR’s on the Erode market street. To get to his shop EVR had to pass him. Not a day passed without EVR picking a fight with him. Iyer would say: “Everything is fate. Whatever happens is fated.” “So you agree, that no matter what happens; it’s fate?” said Periyar. He agreed. The shutter of Iyer’s shop was held up with a stick. Periyar took the stick out and the shutter fell on Iyer’s head. Iyer was furious. “Don’t blame me,” Periyar said. “Fate has brought the shutter down on your head.”

The policing of the boundaries between purity and pollution is partly what we mean when we say Brahminism has never been the exclusive practice of Brahmins. Those who accuse Periyar of hate-mongering, of singling out Brahmins, forget that he was raised by non-Brahmins with the same practices. There were times his mother would not touch him because he did not follow the intricate configurations of bathing and fasting, or stick to the method of storage and use of vessels that allowed one to stay clean. It also was not lost on him that, for his father, staying pure was connected to his own class mobility, with money; he could see, in other words, that his family’s ascetic practices were connected to their sense of mobility and status. In a small, intimate way, he glimpsed the relation between Brahminism and capitalism.

At the beginning of his political life, Periyar was not antagonistic towards Brahmins and nationalists. In 1919, when he left his position in Erode, he was against the Justice Party, of which he was to become president decades later, instead joining the Madras Presidency Association, a branch of the Indian National Congress. A speech he gave that year at the second annual conference of the organisation, quoted in Cuyamariyatai Camatarmam, reveals how drastically his views had changed by the 1950s: “To insult Brahmins in the name of the good of the nation is actually to betray it. Whatever crimes we have accused Brahmins of, the Panchamars and their like have accused us of. Why doesn’t the Vellalar who wants to eat with Brahmins also want to eat with Panchamars?” At the time, his understanding of caste was individualistic, and he thought, along with Gandhi, that it could be worn away by personal introspection.

Periyar was among the many who, having given time, energy and money—even going to jail—for the nationalist cause, were hurt by Gandhi’s order that the Non-Cooperation Movement must stop after protesters burnt down a police station and killed 23 policemen at Chauri Chaura, in Gorakhpur district, in 1922. After popular resistance was suspended, a new faction of the Congress called the Congress-Khilafat Swaraj Party—led by, among others, Motilal Nehru, Vitthalbhai Patel and Chittaranjan Das—decided that the way forward was to contest for the limited electoral positions set up by the Morley-Minto reforms of 1919. In Madras Province, the party was led by two Brahmins: S Satyamurthy Iyer and S Srinivas Iyengar. Periyar became disillusioned with the Congress. To him, entering electoral politics showed that Congress leaders were not representatives of the peoples’ interests but a caste elite seeking to become a political class. Geetha and Rajadurai quote the scholar and activist Thiru V Kalyanasundaram on how Periyar’s views began to shift:

From the day the Swaraj party was born a kind of bitterness about the world of politics came over Ramaswamy Naicker. Slowly he began to change. I realised it was his honesty that forced him to change. He felt that with the Swaraj party the spirit of non-cooperation was lost and a mere chasing after titles and positions was left. He said the Swaraj party would elevate Brahmins and bring down everyone else.

Although the members of the Swaraj Party claimed that putting themselves in official positions was the most effective way to fight the colonial government’s authoritarianism, the party only won 42 out of 105 elected seats in the central legislature in 1923, with a further 40 members nominated by the colonial government. This did not afford the party leadership much power to pass or block legislation. The actions of the newly appointed Indian ministers and judges convinced Periyar that the national movement only served the interest of a privileged minority—Brahmins—and that the abolition of untouchability was inextricably linked to the abolition of Brahminism. An essay by Ko Raghupathy in his book Dalit Potuvurimai Porrattam—The Dalit Struggle for Civil Rights—describes one such instance in detail.

In August of 1924, a bill was introduced by the Justice Party’s Rettamalai Srinivasan, one of the few elected officials from the Depressed Classes, granting Dalits the right to walk in the agraharams and dominant-caste streets of villages in the Madras Presidency, as well as the right to make use of all public wells, canals, and buildings. In Palakkad—the district with the highest concentration of Tamil Brahmins in the country—the Ezhava (toddy-tapping) community, who for decades had been fighting for their right to walk in the caste-Hindu streets, celebrated the new law. But in November of that year, Ragupathy writes, they were attacked by a group of Brahmins and Chettiars for exercising their new rights during a temple festival. Despite protests in Palakkad, as well as in Kenya and South Africa, the government took no action against the attackers.

In 1925, Rishi Ram of the Arya Samaj wrote to the divisional magistrate seeking justice. The magistrate replied that, although the Ezhavas had the legal right to enter the agraharam, they should nevertheless refrain if it was a problem for the Brahmins and other upper castes living there. In defiance of the judge’s order, Rishi Ram and a group of Ezhava men entered the agraharam, only to be attacked by the Malabar Special Forces and arrested under Section 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, which allows the district administration to penalise unlawful assembly. After the arrests, the court issued a mandate. Yes, all people had the same right to make use of public roads, but who decided, finally, which roads were public and which were private? If to get to a main road or to attend a concert, it was necessary to walk through the agraharam, then the Ezhavas had every right to do so. But it was not the job of the local government to protect them if they went walking through the agraharam for no reason. And so, the residents of Kalpathy Agraharam’s right to practise untouchability was protected by the municipality—run by mostly Brahmin officials, who also ensured that they continued to receive public money.

Around that time, Periyar took part in the Vaikom Satyagraha, organised by the Anti-Untouchability Front led by TK Madhavan and KP Kesava Menon. The struggle succeeded in winning the Ezhavas the right to walk in the streets around the Vaikom Temple, but not the right to enter. Gandhi is often given credit for this, but he was not as crucial to the struggle as is often thought. When Gandhi came to Vaikom, the struggle had been going on for some time. The maharaja of Travancore, alive when the protests began, had died. Periyar and 18 other protesters had just been released from a month in prison.

In a 1953 speech commemorating Vaikom, this is how Periyar recalls it. The queen had expressed an interest in negotiating with Periyar, but a Brahmin minister in her court wrote a letter to the Congress leader C Rajagopalachari saying the queen should not speak to him in person. Rajagopalachari, thinking that the popularity and repute that would come from the negotiation ought to be Gandhi’s, wrote him a letter calling him to Vaikom. The queen told Gandhi she was willing to make the roads public, but was afraid that, if she granted them that right, then they would demand to enter the temple. The day of the negotiation, Gandhi visited Periyar to tell him that the Front needed to give up asking for the right to enter the temple.

Gandhi’s and the nationalists’ willingness to placate elites convinced Periyar that separate electorates were the only immediate way forward for the Depressed Classes. When, at the Congress’s Belgaum session in 1924, Gandhi reconciled with the Swaraj-Khilafat faction of the Congress, Periyar began to write articles under the pseudonym Cittiraputtiran—son of history—criticising Gandhi’s Harijan Seva for having separate wells dug for Dalits in villages and the preponderance of wealthy Brahmins in the Congress’ higher positions. Geetha and Rajadurai quote him as saying:

That Brahmins, ‘paraiyans’, ‘shudras’ shouldn’t draw water from the same well, go to the same temples, that we have to build separate wells and tanks, temples for each — that’s what Gandhi’s plan is; I know it. I dare anyone to tell me different…. When I was head of the Tamil Nadu Congress Committee Task force we got sent a grant of Rs 48,000. For what? Segregated schools for Paraiyans, Pallans, Chakkiliyans, separate temples. Don’t go inconveniencing upper castes.

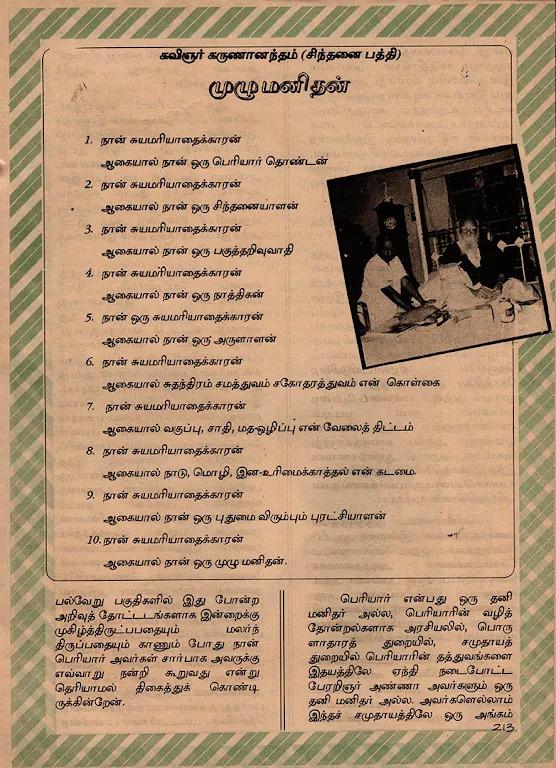

In 1925, Periyar left the Congress, began gradually to work with the Justice Party and started the Self-Respect Movement. By “Self Respect” Periyar meant the erosion of the feelings of wretchedness that he felt Brahminism had caused so many to internalise. He admitted that this was long-term work, and the movement dedicated itself more to education than to reforms. “I have tried,” Geetha and Rajadurai quote him saying, “to turn a mountain upside down with a strand of hair.” The views propagated by the movement differed vastly from those of the party Periyar had just quit. They refused, for example, the polarised notions of masculinity and femininity that gave the Indian nationalists a language to describe India: men figured as warriors or saints, women as devotees, as mothers or widows. In their conferences, they tried to show there was nothing inexorably masculine about anger and nothing inexorably feminine about docility. In contrast to the nationalist “women’s reforms,” Periyar did not believe that men could liberate women.

In a paper titled “Periyar, Women, and an Ethic of Citizenship,” Geetha describes how women in the movement, such as Neelavathi and Meenakshi, propagated that the man-woman polarisation was linked to the one between Brahmin and non-Brahmin, as well as that between capitalist and worker; that, in other words, caste and capitalism were linked to reproductive heteronormativity. Neelavathi argues that, as Shudras are denied the status of workers because their work is ascribed to nature, so are women denied the same status for domestic labour.

While the nationalists believed all three structures ought to be preserved, the Self-Respect Movement sought to annihilate all of them. Periyar’s ideal was no marriage at all. In his view, love marriage and mixed marriage still meant forming families, and with families inevitably came private property, inheritance, individualism and competition:

There is no difference between the Brahmin-Shudra division and that between husband and wife. It is the same structure ... The only way out is to make marriage against the law. It is the institution of marriage that turns us into husbands and wives, turns women into slaves.

He was very impressed, during his trip to the Soviet Union in the mid 1930s, with the family organisation he saw there:

no man or woman has to sacrifice themselves to any rule or compulsion … There’s no conforming to law, the country’s customs or its religion. Without all that how can there be a proper way of marrying? There’s none. A man and a woman who want to be together say “We’re friends now” and it’s done.

In practice, the movement focussed on campaigning for inter-caste “self respect” marriages, widow remarriage, the right to divorce, the end of child marriage, and womens’ education. Given that there are now laws that criminalise interreligious marriage in parts of India, the self-respect marriage, with its vows that begin “Today we begin our life together based on love,” is a more valuable institution than ever.

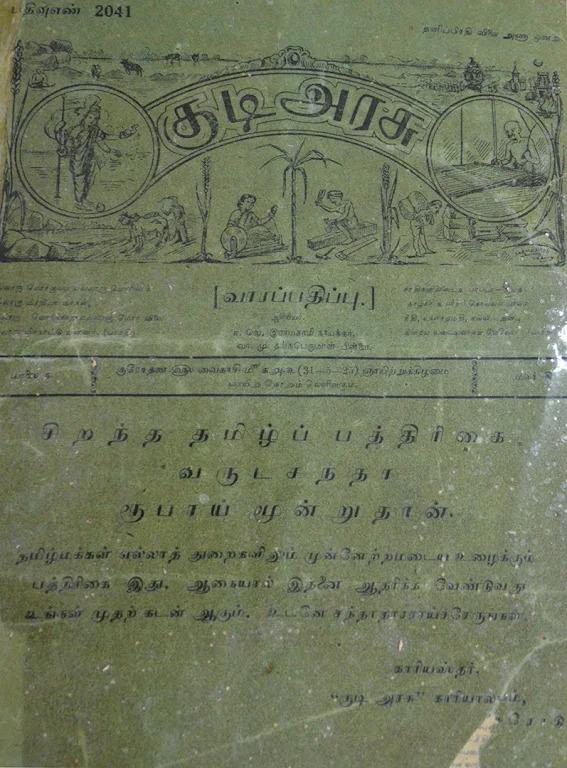

IN THE MID 1930s, the looming possibility of an independent India whose institutions would offer even less to the non-Brahmins than could be won from the British forced Periyar to reckon more with immediate questions of political power and agency. The Self-Respect Movement and the Justice Party merged during the anti-Hindi agitation in 1937, with Periyar as its leader. The demand for a separate “Dravida Nadu” did not stem from race pride, a charge often levied by critics of Periyar. It was a reaction to the denial of separate electorates to the Scheduled Castes. Periyar was one of the few anti-caste leaders who stuck with Ambedkar in the fight for separate electorates. He wrote, in 1932 in Kudi Arasu, that, “In fact, fearing that Gandhi would die, if the separate electorate for untouchables is withdrawn, then we are sure that it’s like sacrificing seven crore people’s lives to save one.”

Periyar started talking about a separate state in 1937, well after the Poona Pact of 1932. The opposition to Independence did not come from love of the colonial government, of which Periyar was very critical. He merely saw how, throughout the colonial period, the Indian nationalists took every small incremental increase in power as a chance to lash out at the people. The Congress won a resounding victory in the first direct elections in 1937. The year also marked the beginning of a two-year wave of mass peasant and worker resistance, especially in Bihar and the United Provinces, and their newly elected governments came down heavily on the people. They had made many promises to and taken a significant amount of money from the landowning classes.

The Congress found itself using the same laws against its own people that the British used to crush the independence movement: the law against sedition and the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act. A speech given in Kolampalayam, titled “Is India a Nation?” and published in the magazine Paguttarivu—Rationalism—shows that Periyar did not let their hypocrisy go unnoticed:

Not even comrade Jawaharlal Nehru has said what self rule means. But if you ask him one day he’ll say it’s opposing colonialism, he’ll say it’s destroying British rule; on another day he’ll say it’s the rule of the proletariat, the rule of the natives. On yet another day he’ll say it’s equality, on another that it’s complete autonomy. Some days he says it’s international socialism. Every day he says whatever comes to his mind depending on who he’s talking to. Comrade Gandhi sometimes says it’s Ramarajya, sometimes that it’s the living according to the varna rules. Sometimes he says there’s space for kings and lords in an autonomous state or he tells you to do the work your caste was meant to do. One day spinning your own cloth itself is independence, wearing khadi clothes is independence. Last month he said ‘If a trace of bitterness comes between the British and us I’ll give my life to make it go away.’

THROUGHOUT INDIA, THE DRAVIDIAN MOVEMENT is most identified by the anti-Hindi agitations, but it did not begin with them, and many other organisations were involved. It is usually seen as an extreme expression of racial pride and a refusal to cooperate with the movement for India against British colonialism. In reality, it was a response to an attempt by Indian nationalists to disenfranchise the majority of the Tamil people. The imposition of Hindi was, and is, not just an attack solely on Tamils, but an attempt to subjugate the majority of the Indian people.

During his term as chief minister of Madras, between 1937 and 1939, C Rajagopalachari’s government closed down over two thousand rural schools set up by the Justice Party, citing a lack of funds, and, at the same time, started several schools to train Brahmins to chant the Vedas. In a province where less than fifteen percent of the population was literate, and probably less than five percent literate in English, Rajagopalachari had promised that, during his tenure as chief minister, he would make learning Hindi compulsory for all students. According to Geetha and Rajadurai, he declared at the Hindi Sahitya Samelam:

[The industrialist] Jamnalal Bajaj asked me what I would do for him if was elected. I said I would make Hindi compulsory on the school finals. It is not wrong to force them as a mother must sometimes force her child to drink her milk. The Tamil language is like one’s feet. Hindi is a car. English is a train.

In August 15, Rajadurai argues that Hindi imposition was never about administrative efficiency or national unity but instead about the creation of an all-India market for the Congress’ industrialist donors, such as the Tatas. Their campaign to spread the national language was very well funded, not only by businessmen from further north, but by the Marwari merchant community in Madras as well. Since those who knew Hindi there already were Brahmins, imposing Hindi would let two percent of the state’s population keep government jobs and college seats to themselves. Satyamurthy Iyer, another Brahmin leader of the Congress, went even further in a speech quoted in Kudi Arasu in 1939:

If I come to power I’ll make not only Hindi, but Sanskrit too compulsory … Ramrajya must be realised while Gandhiji is still alive, and Ramrajya is nothing other than living according to your varna, doing the work your caste was born to do.

Another development to reckon with was Gandhi’s Wardha Scheme of Education, which prescribed that the government educate all children from the ages of seven to 14 in their mother tongues, with Hindi as a compulsory second language. English would not be taught. Education was to focus on some kind of craft supposedly appropriate to the child’s capacity and the community’s needs, such as fishing or leatherwork, and to be taught fast enough that the children could make products for sale that would help meet the schools’ expenditure. Girls were to be given the same education as boys for the first four or five years, after which they would focus on “Home Science.” The conglomeration of the industrial, landowning, and political classes, what many now refer to as “the Brahmin-Bania nexus,” had recognised that the most powerful weapons Shudras and Dalits could wield against their authority were the English language and Western education. Gandhi’s push for what he called “basic education” was a blatant attempt to keep the lower castes in servile, menial jobs, while men from the elite castes, who would go to private Western-style schools and learn English, became doctors, lawyers, engineers, and civil servants. The 2020 New Education Policy’s promise to erase the boundaries between “skill-based” and academic learning is alarming but old, and even the campaign to impose Hindi and Sanskrit is not letting up. Periyar’s words from a speech given in Madras in 1957 ring true even today:

Can we take a place among the world’s peoples without learning English? How many new experts, intellectuals, artists and artists have emerged from us learning English? It is clear that we are now at the gate of history. But who has become knowledgable or progressive from learning Hindi? It teaches nothing but orthodoxy and fanaticism. In fact, it’s a language produced solely for the Godses that killed Gandhi.

The first anti-Hindi agitation mobilised unprecedented numbers of people of disparate organisations and ideologies, including many members of the Congress. Crowds demonstrated not only in Madras, but in Singapore, Eelam, Burma and Malaysia, and new transnational networks of magazines and papers came into being. For the first time, thousands of women joined the Self-Respect Movement’s conferences and demonstrations.

The protesters were non-violent. Most limited themselves to shouting slogans; a few went as far as fasting. The laws they were arrested and punished under—Sections 505(1)(c) and 124A of the Indian Penal Code—forbid inciting hatred between groups on the basis of class, religion, or language. By 1939, 683 men and 36 women had been jailed, all of them sentenced by the same Brahmin judge in Georgetown, SR Venkataram Iyer. Two of the men imprisoned— S Natarajan and Thalamuthu—died in jail.

Periyar, made a high-security prisoner in 1938, was released in less than a year because of his deteriorating health. While he was in jail, he was elected head of the Justice Party. That was when the party and the Self-Respect Movement merged to form what, in 1944, would be renamed the Dravidar Kazhagam.

THE POLITICAL THEATRE DEVELOPED during the first anti-Hindi agitation—the metaphorisation of Tamil as a mother ruined or desecrated, the revivalist celebration of kings and mythological figures from the Tamil past—constitutes, for many, the extent of Periyar’s thought. This understanding has been reinforced by later iterations of the Dravidian movement, who have made it the centre of their political vision at the expense of programmes Periyar thought more important, such as socialism, atheism and the abolition of marriage. Burning Ram effigies, breaking Ganesha idols and publicly celebrating Ravana were strategies to mobilise people quickly and in large numbers against the pressure of Hindi imposition; however, they were not central to Periyar’s political vision. Later, Dravidian ideologues such as M Karunanidhi built their politics on a glorified vision of the Tamil past. Karunanidhi painted Kannagi as Tamil Nadu herself and claimed filiation with the medieval Chola kings.

The Martinican author Édouard Glissant writes in Poetics of Relation, “Most of the nations that gained freedom from colonization have tended to form around an idea of power — the totalitarian drive of a single root — rather than around a fundamental relationship with the other. Culture’s self-conception was dualistic, pitting citizen against barbarian.” The root, Glissant says, takes in all the surrounding water and nutrients for itself at the expense of everything around it. Nehru, as a brief look at his Discovery of India shows, considered India the driver of a single race that prospered, not by engaging, but by keeping a distance from the other.

The book was written under extreme conditions: nearly three years of imprisonment at the height of the Second World War and the movement for national independence, the last push to claim what Nehru thought of not only as the fruit of decades of labour, but as an inheritance to be passed on to his children. It is a romantic book, its tropes the usual ones: the spirit or soul of a race, history as the inevitable movement toward greater freedom of that spirit’s absolute realisation embodied, finally, in a state by and for its people. It is also romantic in a more individual sense, about a leader discovering himself, establishing a metonymic relation between his own destiny and the destiny of a people. (In a traditional, literary romance, a hero from the nobility both restores and establishes more fully the rule that is their divine right by defeating an enemy, an other. In the Old French Song of Roland, for instance, the enemy is the Muslims in Spain. In Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, it is the Welsh.)

That is why, though Nehru cloaked his rage with words like “society” and “civilisation,” he experienced Periyar’s 1957 demonstration as a visceral threat. No one who reads “more primitive than the most primitive tribes” will fail to recall these lines from the Discovery: “The word Arya … came to mean ‘noble’, just as unarya meant ignoble and was usually applied to nomadic tribes, forest-dwellers, etc.” Or the interpretation he gave his daughter, Indira Gandhi, of the Ramayana: “In the Ramayana, we are told that Rama was helped by monkeys … It may be that the story of the Ramayana is really a story of the fights of the Aryans against the people of the south, whose leader was Ravana. Probably the monkeys were the dark people who lived in South India.”

Periyar’s rationalism led him to dismiss the past and his culture entirely. He dismissed not only all “Hindu” Tamil literature, but also “pre-Hindu” literature, such as the epic Silappadikaram, saying in a speech in Salem in 1951:

As soon as this woman [Kannagi] got angry she ripped her breast off and threw it? What kind of an idea is this? Can you rip your breast off your body? A situation like this hasn’t been described anywhere other than the Silappadikaram, If you throw your breast will it catch fire? Is there phosphorous in it? What is the use of all these imaginings and superstitions?

He took pride in Tamil only when it was pitted against Hindi or Sanskrit, saying, in 1936, at Madras’s Pachaiyappan College that “I don’t have any special attachment to Tamil or any feeling about it separated from the self respect and prosperity of the Tamil people. I think if we want it to advance and become a world language, we have to break its ties to god and religion … Even our grammar is bound up with religion.”

In many of his speeches and writings, Periyar points out that the word “Shudra,” when used colloquially, means “illegitimate child” or “child of mixed blood.” The children born out of the systematic crossing of caste boundaries constitute their own class. Shudras disturb upper castes so much because they are a reminder that no caste’s purity has been absolutely preserved, that everyone’s blood is so mixed that they can no longer be traced back to their pure origins. They are a constant threat to the nationalist fantasy of war without rape, slavery and concubinage, the very fantasy that consecrates race and war as nationalism’s sacraments.

Periyar, grappling, like Nehru, with colonialism and the violent past, imagined, not a Dravidian counter-image of India, but a kind of anti-nation, a society ordered by rationality and transparency instead of lineage, myth and the obscurities of affect. He insisted that we could, and needed to, go into the future taking nothing of the past with us, cutting ourselves off entirely from our roots. But, unlike Ambedkar, who, at the end of his life, swapped his sharp, critical mode for parables and tales in The Buddha and his Dhamma, Periyar, as the Dalit critic D Nagaraj points out in his essay The Problem of Cultural Memory, never tried to give us a language with which we could imagine a new world. When Periyar takes on the Silappadikaram, he does not read it on its own terms, but rather, only through the lens of his own intense materialism. But annihilation may not be a project of aggressive distancing; it might require a critical intimacy with the past.